The McClellan Controversy (Continued)

Student and Faculty Protests Begin

McClellan was a popular teacher, and the students overwhelmingly backed his side in the case. That, combined with the administration’s repeated refusal to meet with student or faculty groups and the statements being released by community and faculty organizations protesting the decision meant that students soon began to question the administration. On October 11, the first mass student meeting occurred at Kaye Auditorium to show support for the faculty’s actions in support of McClellan. Over 1500 students attended even though an anonymous person had called the radio station and told them that the meeting had been moved to another date. Student government leaders Don Keskey and Rob Fure presented the “Facts of the McClellan Case”, a document issued by the Faculty Senate. They also called for short-term and long-term forms of protest. Short term actions included writing letters and telegrams to political officials, demonstrating, and picketing. If this did not resolve the issue, Keskey suggested that class boycotts could be a long-term plan. Students and faculty began “round-the-clock picketing of the Interim President’s home and office.”

On October 13, Johnson announced that he would “reopen a review of the status of Dr. McClellan.” The students and faculty, hopeful that McClellan’s termination would be rescinded, ceased protesting in the hopes of easing the situation. On October 17, Johnson gave a press conference which “repeated, amplified, and made public the four reasons reportedly offered on October 9 for the action taken against Doctor McClellan.” In his statement, he also claimed that other administrators and Anthony Forbes, the head of the history department had agreed with Harden’s decision.

The next day, October 18, students resumed picketing on-campus at Johnson’s office. That night, they held another mass meeting in the Hedgcock Fieldhouse. At it, they verified Dr. McClellan’s claim that he had not encouraged them to sue the university and had instead told them that “every man must follow the dictates of his conscience and accept the responsibilities of his actions.” McClellan also spoke to the students at the meeting. Meanwhile, the faculty overwhelmingly voted (197 to 17) in favor of re-instating McClellan and officially disapproving his firing and sent telegrams to state officials asking them to take action. They also voted to express their approval of how the students were handling their protests. Forbes, the professor whose evaluation had been quoted to condemn McClellan, announced that he fully backed McClellan’s case and that he had “rarely seen a finer teacher in action.” The faculty worried that any review would go against academic freedom since the Board of Control consisted of businessmen who would “demand…corporate loyalty” from teachers. The Faculty Senate also went on TV to read their statement about why they disapproved of McClellan’s dismissal.

The students, however, saw themselves and not the faculty as the real leaders of the movement to save McClellan. The Editor of the Northern News wrote that people on both sides of the issue “[had] long since cut off their heads and started thinking with their guts,” as seen at the general faculty meeting where the faculty were “embroiled in a three hour harangue over a sleepy motion by Dr. John Allswang.” The Editor concluded, “There can be little doubt that student leadership under Don Keskey and Rob Fure has been able to do considerably better. They have been able to do what the faculty leadership hasn’t. They have left both of their mass student meetings with agreement on a reasonable course of action.” The Editor further urged students in another editorial that even though “the adult leaders of the University have failed to be reasonable with each other in settling the conflict,” students must “be careful not to let [themselves] use that as an excuse to abandon rational behavior.”

That weekend, twelve students traveled downstate to Lansing to picket Story, Inc., the company at which Harden was now President. Harden told the Northern News that “A couple of the students came over to our home…and we spent some time talking the whole thing over. I told them they could picket as long as they wanted and when they got cold they could come in for coffee. Just so they could go back and tell whoever sent them that I wasn’t changing my position.” Many students who did not make the trip downstate demonstrated at a football game on campus. That weekend was Parents’ weekend, and students took the opportunity to pass out literature to the parents about the McClellan case. Some of the parents reportedly joined in with the students at the half time protest. On October 24, Harden released a statement in which he implied that the reason he fired McClellan was that he “would not add in a scholarly way to a department that is sorely in need of improving its scholarly output.” He said that “the question of academic freedom is not the real issue in this controversy. The real issue centers directly on the question: Who is going to run the university?...My own conviction is that the Board of Control cannot and should not abdicate from its legal responsibilities as defined in the Constitution of Michigan.” He concluded by urging students “not to become tools of those who for selfish reasons would destroy your university.”

Two days later, over two thousand students gathered to discuss what they would do about the firing of McClellan. Dr. Barnard, who had previously led Vietnam protests and who planned to resign with several other faculty members if McClellan didn’t get his job back, spoke at the meeting. He explained why he believed each of the charges against McClellan were false and that most of the faculty would not penalize students for boycotting classes the next week. It was then that the students began to plan the infamous “McClellan Week.” Local lawyers warned that protests, even those done “in good conscience,” could harm McClellan’s case in court, but student decided to go ahead with the protests anyway.

Protesting the Second Review of the Case

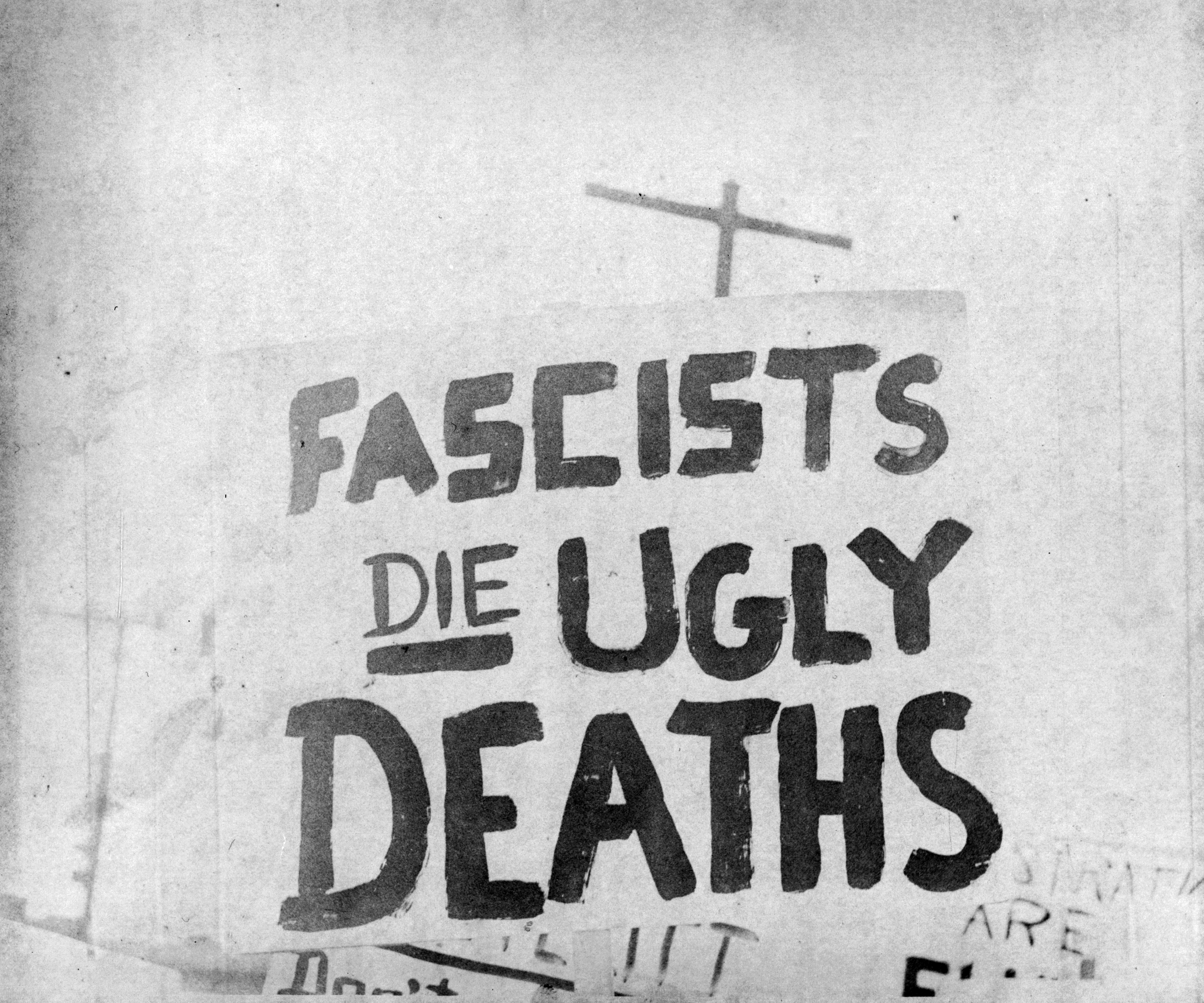

On October 25, the same day as the meeting at which students came up with the idea of McClellan Week, Johnson and the Board of Control conducted “a complete review of the case”. University police barred the doors near the rooms in the University Center (UC) where the Board was meeting. Students, whose numbers varied between twelve and fifty throughout the day, “chanted, sang, and tapped on the walls” while the Board ate dinner. Later, they circled the UC trying to figure out which room the Board was in. Eventually, they were allowed into part of the UC to protest. The Mining Journal reported that “Sign carrying students were loud but orderly, interspersing Christmas carols and patriotic selections with ‘We Shall Overcome’ and chanting ‘Hey, hey, Ogden J., how many profs have you lost today?,” referencing the resignation of several professors upon learning of the firing of McClellan. Sixty other students split their protests between Johnson’s office, Kaye Hall, a cafeteria, and the Charcoal Room in the UC.. One professor who was aiding in the picketing of Johnson’s office, Vernon Pierce, was almost arrested by police for sitting in front of the office door. One “unidentified woman” told students that as the Board had yet to make a decision about McClellan, “they had an obligation to wait until the board’s decision was announced and not get involved with police.” The protesters agreed and went to Kaye Hall, where they sat on the steps and listened to Vernon Pierce give a speech “urging immediate action.” Picketing of Johnson’s office then continued.

The next day, the Board released a statement reaffirming their decision to fire McClellan, stating that though it recognized “the sincerity and intensity of convictions…expressed to it,” it was “aware of the need…for preserving the integrity of its administrative powers.” As some would point out in Mining Journal editorials in the coming days, “Integrity itself means merely adherence to a code. Does this imply that the code of the Board of Control for Northern Michigan University is based primarily on power?...The board referred not to a code of justice, not to a code of truth, but to a code of power.” In an attempt to appease the masses, Johnson created a joint faculty-administration committee to investigate all faculty concerns and to improve communication between faculty, administration, and students. It didn’t work.

That same night, October 26, 2200 students gathered in Hedgcock Fieldhouse to protest the decision. Student leaders and faculty spoke about the facts of the case and asked the crowd what the course of action should be. The demonstration began with a presentation of the “Edgar L. Harden Memorial Award” for academic freedom to the students. One faculty member called for the resignation of Johnson and the Board of Control, stating that it was the only way that NMU “could be a great university.” After the formal event, students moved to Kaye auditorium to listen to bands and folk singers. “As many as 3000 students” attended the all-night demonstration in Kaye. The Mining Journal described the scene in a slightly condescending and incredulous manner:

Songs of freedom opened the “concert,” followed by a variety of selections, speeches, and general noise. Rolls of toilet paper and hand towels and stacks of IBM cards were tossed about the auditorium as students chanted “Hey, Hey, Ogden J., how many profs did we lose today?” In the overcrowded hall, students were sitting on the floor, in the aisles, on the stage, and were hanging from the heavily over-crowded balcony.

Women were given no hours for the night, so many returned with mattresses and pillows and moved back to the Fieldhouse “with their bands and mattresses, blankets and pillows.” The demonstration did not end until 7 AM.